Presented at the Depression in Popular Music Conference – Sorbonne University Pierre Louis Institute of Epidemiology and Public Health – 27/06/2025

This paper is about how we locate depression, and what depression is when we talk about it being in popular music. The intention is not simply to be pedantic about the choice of prepositions, however. But the positioning of depression in popular music, offered by this conference, provides an opportunity to reflect on the construction of this object of study as constituted by overlapping disciplines that seek to tease out the entanglement of popular music, its associated practices and mental health. What I want to claim here, through a line of thinking that draws on the psychoanalysis of Jacques Lacan, the post-psychoanalytic theory of Deleuze and Guattari, and contemporary psychodynamic clinical theory, is that depression cannot be considered a discrete condition but rather a symptom of a particular relationship between desire, the construction of subjectivity and the environment.

Following this psychodynamic thinking, depression is considered a symptom of inwardly directed anger. That is anger that the subject feels towards something in the world that they feel unable to direct outward or impotent to do so in a way that they desire, and have thus redirected it towards themselves. This is perhaps to protect themselves from the danger of attempting to attach to a hostile world in which they feel powerless to assert their desires, which feeling itself can result in yet more inwardly directed anger.

A similar relational scheme of, desire, the construction of subjectivity and the environment might also apply when giving an account of what we mean when we talk about popular music itself, which can be thought of as emerging from these same fields as an audible direction and mediation of certain routes of desire.

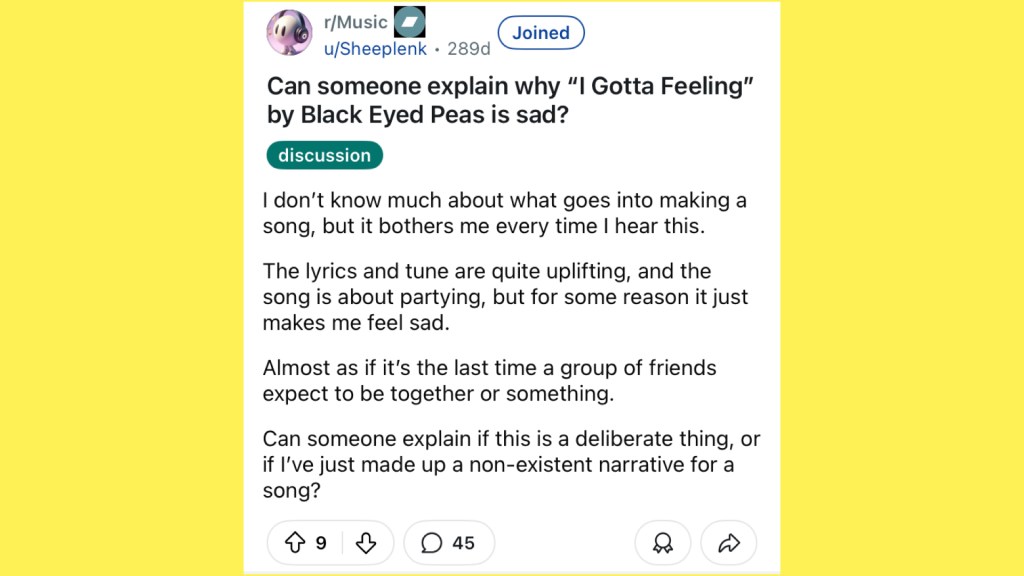

Thinking about depression in popular music like this, I claim that depression is not something that a subject possesses but a description of a particular shape of the movement, or lack thereof, of desire through a subject in relation to their environment. So, to the extent that it is in popular music, it is only that this music is in relation to some kind of situation and subjectivity, all of which are in flux. To illustrate this claim, I want to talk about a song that I am not alone in finding incredibly depressing, “I Gotta Feeling” by the Black Eyed Peas, which needs a little more context.

We are living at a moment of crisis levels of anxiety and depression all over the globe. This is often attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, but I would claim that this simply unleashed a tendency that was already underway. A tendency I claim was intensively set in motion during the global economic depression that started in 2008, the year before the release of “I Gotta Feeling” in 2009, and from which the Western economies have never really recovered. Here, I want to think about how desire moves through this song. I want to illustrate the depressive paths or loops it takes and, in other forms like anger, how these loops continue to shape the emotional and concrete reality of the present.

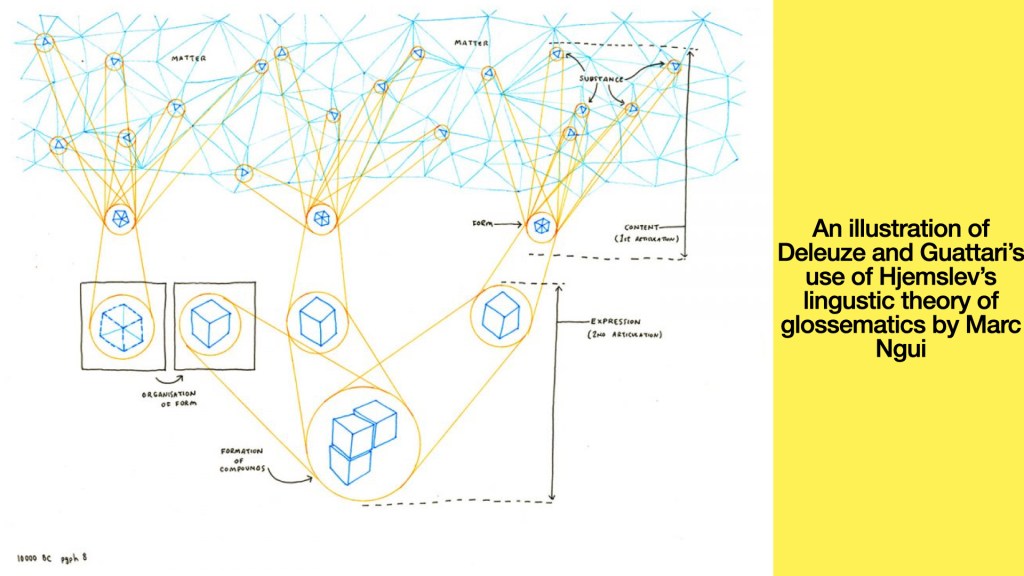

This is not to claim the song’s responsibility for or representation of depression; rather, I want to consider it through the glossematic concept of expression. That is to understand meaning not as something that only works through the interpretation of representation, but as carried through the force of formed substance. (This is also where I should mention the influnce of Fred Moten and his critque of the understanding music as textual, rather than a resistant object but much like Glossematics this needs much more space to unfold)

Or put another way, following the work of Robin James in Resiliance and Melancholy (2015) on the economic figuration of soars and drop in EDM, I want to consider how depression can be in popular music that does not seek to represent depression or without gesturing to a necessary relation to the psychological status of the artist.

Instead, depression in popular music can be understood as the turning inward or redirection of desire/agency as anger to a state of inertia that emerges from a societal depression mediated across economic conditions, political impotence and social alienation.

In a sense, I owe the trajectory of my work and thinking more generally to “I Gotta Feeling”. I once discussed the song with my late supervisor Mark Fisher, and about it he said “It’s so fucking bleack it’s like Samuel Beckett”, but before that, It was released the year after I started my undergraduate degree in Creative Music Technology. It was played constantly at the Student Union night club, Rubix, which was the only place in the posh commuter town of Guildford where we could afford to go out while accumulating debt for our education. Not that the premium prices for entry and drinks elsewhere in the town would have meant the playlist was any different. Thinking back, I should have gone to London more often to hear more of what I was looking for. But I didn’t. And so I did something else.

Riddled with an anxiety that is not uncommon, especially among middle-class white boys infatuated with the idea of their own goodness, I had trouble relaxing into the forced fun of the nightclub. The story I was spinning was that this dance floor was a meat market for predatory men to seduce “girls” who just wanted to dance with their friends. So, feeling a mix of emasculation and contempt that was never properly articulated, I would hang out with my similarly awkward male friends, claiming our opting out while being in the club was something about taste. Or I would go and argue with the members of the Christian Union who were handing out free cups of tea outside, about the incoherence of Christianity. But the reasons I did these things, and the reasons I felt bad, reflected a much more immanent incoherence. An incoherence produced by frustrated desire, as anger being redirected from its object and directed inwards towards myself.

Like Adorno and Jazz, I didn’t understand the kind of music that was played in the club. This music wasn’t aiming to produce a feeling of introspection (as distinct from an act of introspection); it was aiming to make reality shimmer with a sense of possibility that would allow people to feel free for the night. This is where, however, below all the obfuscation of my projections and defenses, there was a kernel of insight. Much like feeling introspective is not identical to being introspective, feeling free, while a necessary component, is not identical to being free.

Poorly articulated as it was, and as much as I was also depriving myself of what is a good feeling – feeling free – that can be worth having regardless of its relation to material reality, this scene revealed something uncanny about the culture I was consciously integrating myself into and the world it was a part of.

2009 was the year of the Black Eyed Peas. They had already had major success with “Where Is the Love?”– an anthem that might be about desiring an end to injustice, but is hard to know for sure given the vagueness of its content. But “I Gotta Feeling” was a dance floor filler that was not only enjoyed by millions of people but also seemed to provide its own kind of auto-enjoyment, in that the song is about anticipating the enjoyment of the song while on a night out. This enjoyment-in-advance made it even easier to enjoy.

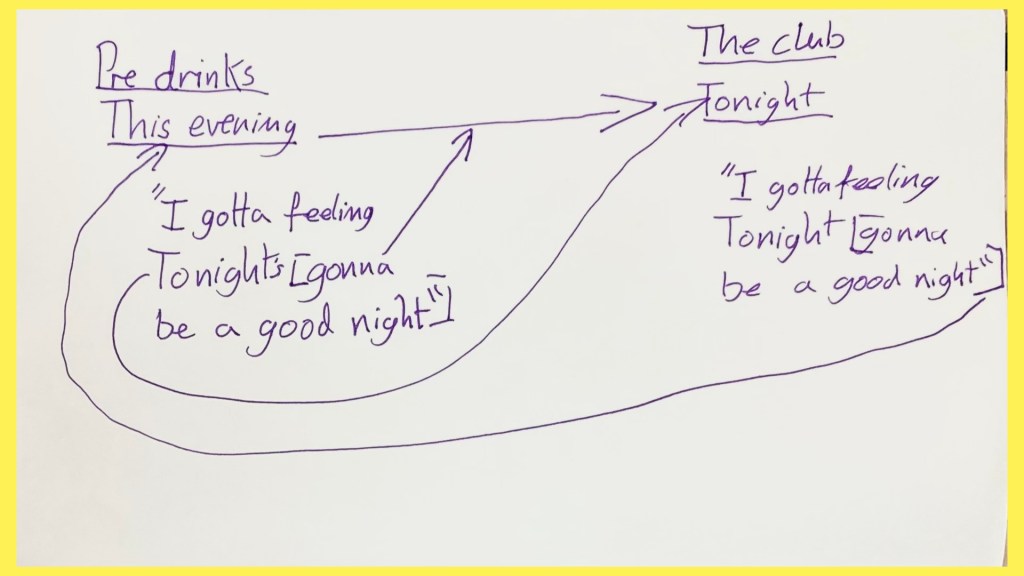

The feeling the song is about is one of excited anticipation expressed as a thought becoming discursive, “that tonight is going to be a good night”. This made it perfect for pre-drinks or pre-gaming. The loop that drives the song could be argued to underline this excited anticipation, taking as it does a ska upstroke guitar sound, treating it like a malleable sample and moving it from the off-beat forward to the beat, making that “good night” sound all the more imminent.

But the song came into its own when the “good night” in question was already underway.Whenever the song was played in Rubix some time between midnight and 3 am, it served as an affective and temporal fold experienced as an earlier desire returning to subjects. It re-injected the enjoyable tension of anticipation back into the enjoyment of release in the present. In that moment, the lyrics and the loop and the strings make the present thicker by making the anticipation of tonight part of the appreciation of what is happening now. The desire to go out becomes part of the desires of already being out.

I can imagine that for those who like the song, or liked it well enough in context, “I Gotta Feeling” being dropped at the right time might have been just the rally they needed to power on through until morning. People may have met and fallen in love, or simply the lust that was right for right then, or into the prolonged heart ache of mistaking the latter for the former, or bonded as a party crew more deeply because that song came on at the right moment and allowed them to invigorate themselves by bringing their former desire in anticipation into their desire to be in the present party.

This was what you had been waiting for. This moment has to be enjoyed freely. You have to feel that tonight is going to be a good night.

While it may be reasonable to assume that The Black Eyed Peas were not aware of the damage that would be wrought by the global financial crisis of 2008, in a certain sense, I think the song carries some kind of material awareness of what is to come.

I claim this in the sense articulated by the French economist Jacques Attali in Noise: The Political Economy of Music (1985). In this esoteric history of music, intoxicated by the thinking on offer from Deleuze and Guattari’s first published fragments of what would become A Thousand Plateaus (2013b 1980), Attali claims that “music is prophecy”. He argues that music’s “styles and economic organisation are ahead of the rest of society because it explores, much faster than material reality can, the entire range of possibilities in a given code” (pp).

Code here is meant as the system of meaning production, which structures material and social relations. Attali’s is a very particular and partial view of history. Furthermore, his opposition of music to material is clumsy, as is the explicit musical exceptionalism. But read generously, this perspective does offer something.

If music and depression can be thought to emerge from the differential relationships of social relations, economic forces, commercial and cultural pressures, technological developments and the formation of subjectivity, then popular music’s particularity might be suggestive of the trajectory society is travelling at a moment of economic trauma. So, as unlikely as it is, that will.i.am, apl.de.ap, Taboo and Fergi had a consciously articulable awareness of what was going to happen; it is fruitful to read “I Gotta Feeling” as expressive of the social and economic depression that was to come in a particular sense.

If depression is the redirection of desire as anger from its external object back into its subject, the depression of “I Gotta feeling” can be found in how it “educates our desire” (Levitas 1990) to perform this motion of redirection in a quotidian setting.

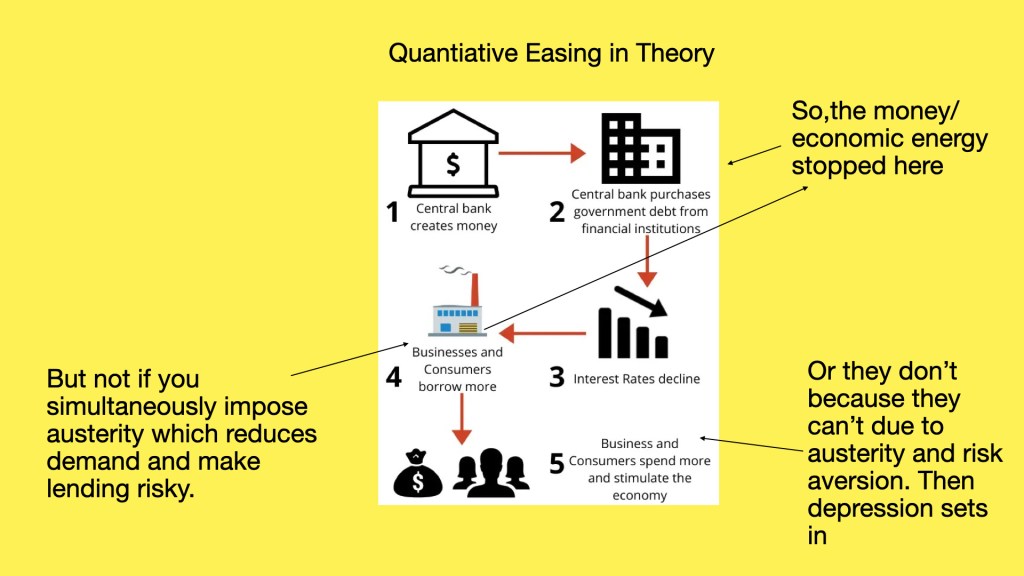

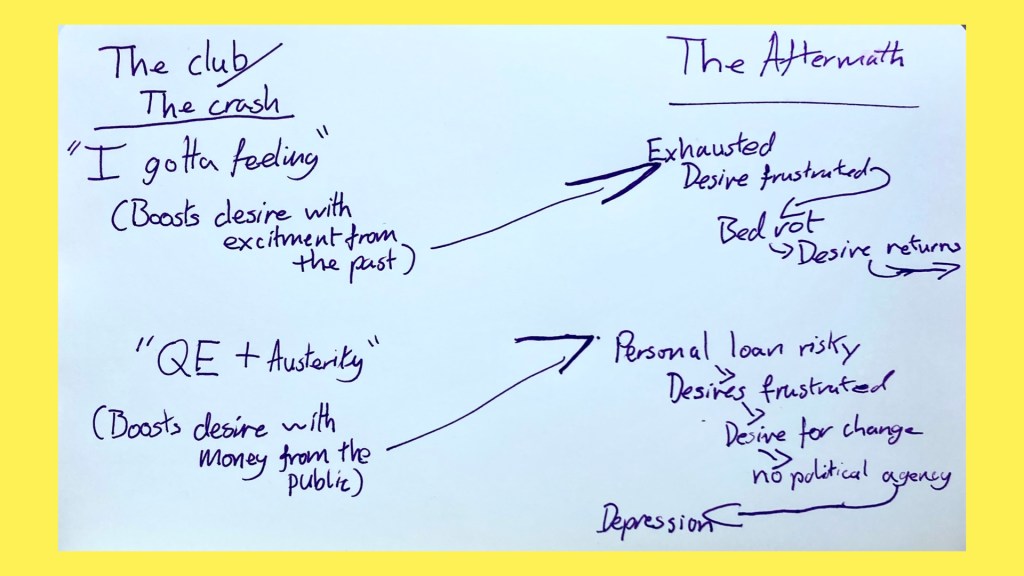

I claim this is most overt in the formal similarity between the auto-enjoyment capability of “I gotta feeling”, and the response of the governments to the crisis as they and central banks enacted a temporal fold of their own in the economy itself, through bank bail outs, policies of quantitative easing, austereity and the lowering of interests rates (Varoufakis 2025). These policies meant that the state effectively tried to performatively induce in the economy the idea that the unfettered investment and growth that had been the norm during the housing bubble could continue. That, in terms of economic productivity, even though the market was plummeting, “tonight is going to be a good night” to invest and grow the economy. In this sense, they tried to bring the excited anticipation of the boom into the angry exhaustion of the crash. To revive the flagging party by folding the affective condition of the past into the materially different situation of the present, and by redirecting the anger about the flimsy foundation of the financial system onto the public through austerity.

When this is done musically to address the exhausted frustration that tonight had not turned out to be as exciting as hoped, the fallout from doing this by dropping a track to boost the flagging energy at the club is an exhausted, usually, young person, whose desire/agency is temporarily spent but who will, likely, recover as they have sources of energy that are exogenous to the music-club-desire relation.

When it is done at the scale of a national economy, the consequences are displaced socially rather than temporally, because money and energy overlap a great deal in political economy. Without an exogenous source of energy/money, the exhaustion of economic auto-enjoyment displaces anger onto the most vulnerable in society through policies of austerity that diminish the agency and desire of anyone whose economic security is subject to the sale of their labour power.

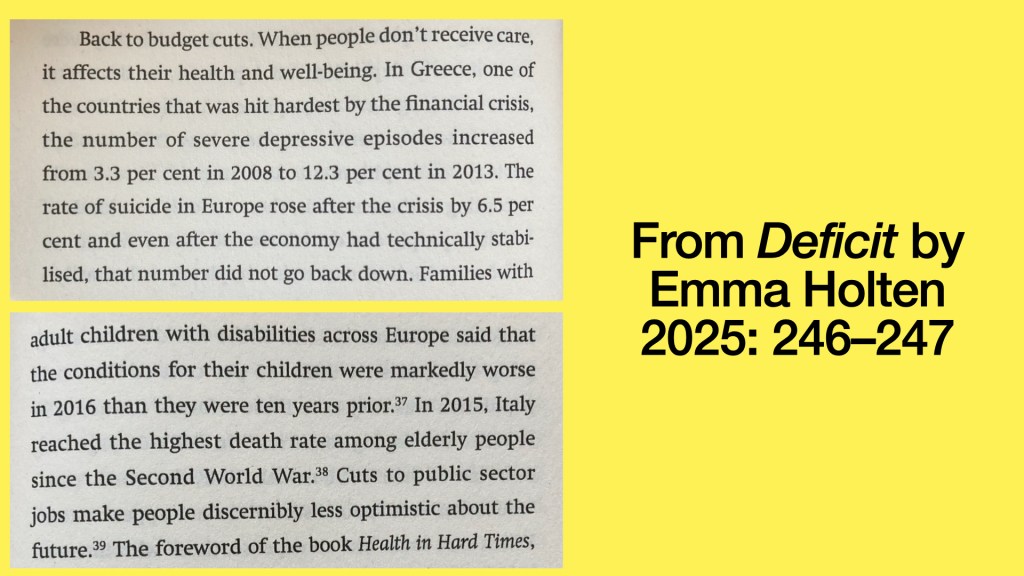

This general policy of economic depression, and its techno-cultural repercussions, would seem to be at least a partial cause for the rising rates we see of mental distress (Holten 2025). This formal parallel is helpful for me to think through the disquiet I felt in the club in 2009. The song and setting carried with them a prophetic depression. That being, the feeling of the disappearance of the future that had been promised by extractive capitalist realism before that future had actually disappeared, as I would claim, ambivalently, it has today, some seventeen years later. So perhaps, even though I was bringing myself down much more than I needed to, the nights at Rubix had an atmosphere of desperation that was more than just me projecting.

For the people who go to university in the global north, those being the globally well-to-do but locally middle class, this period of life is one in which you are allowed to “feel free”. However, the condition of this freedom is gaining a qualification and debt that pressures you to become economically bound to productivity, acceding to the logic of the capitalist market. In other words, this feeling of freedom is, much like the professional managerial class’s euphemism for salaries, compensation for what is to come rather than making up for some unforeseen misfortune that has happened.

When “feeling free” is the compensation for never being free, you have to feel tonight’s gonna be a good night.

What I have argued for in this paper is the idea that when we talk about depression being in popular music, it may be fruitful to consider how it can be said to be in there. While important work has been and continues to be done to investigate the representation of depression in music and the concrete mental health experiences that are surrounded and facilitated by music, it is also worthwhile to ask questions about what exactly we are listening and looking for when it comes to locating the particular inward looping form of desire as anger that psychodynamics would argue is constitutive depressive experiences.

Here, I have taken what could be called a sonic fictional approach to investigate how depressing it can be to listen to music that would have you feel that tonight’s going to be a good night, when tomorrow has been willfully lost on the balance sheet. Such a perspective sees music as able to simultaneously hold in it depression as life-historical and world-historical experience. So, when we talk about depression being in popular music, I think it is as important to think about the routes it took to get in there and where it is going next because depression can show up in places that we don’t expect.

Leave a comment